A lot later than I’d hoped, here’s an article on some of the changes in the Money Laundering Regs that took effect on 1 April 2023. I’ve also covered some anomalies in the PSC regime when compared with AML Beneficial Owners that could trip up the unwary.

In brief, this article explores:

- At what points are we now required to check the PSC register?

- What records are we now required to keep?

- Does the change to reporting only “material” PSC discrepancies now give us a reason for not reporting in many instances?

- Do PSC discrepancy reports need to be repeated if the discrepancy has not been fixed?

- Does an insolvency office holder become a PSC?

- When a PSC is not the same as an AML beneficial owner: (i) when the shareholder is a UK-registered company

- When a PSC is not the same as an AML beneficial owner: (ii) when the shareholder has died

- When a PSC is not the same as an AML beneficial owner: (iii) when the person exercises “significant”, but not “ultimate”, control

The Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (Amendment) (No. 2) Regulations 2022 can be found at https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2022/860/contents/made

In this article, I refer to three useful pieces of Companies House guidance:

- Reporting a Discrepancy: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/report-a-discrepancy-about-a-beneficial-owner-on-the-psc-register-by-an-obliged-entity

- Statutory Guidance on “Significant Influence or Control”: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/675104/psc-statutory-guidance-companies.pdf

- PSC guidance for companies: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/993230/170623_NONSTAT_GU__1___3_.pdf

Reviewing PSCs as part of “ongoing monitoring”

When the MLR19 came out, several professional bodies queried the wording that appeared to suggest that a client’s PSCs were to be reviewed (and, if necessary, a PSC discrepancy report submitted) during the life of a business relationship. It was felt that this put an unnecessary burden on AML-regulated businesses. As a consequence and because it appeared that the MLR19 had gone further than had been originally planned, in 2020 the MLR17 were changed making it clear that a PSC review was required only when establishing the relationship at the start.

However, in 2021, HM Treasury consulted on the question: wouldn’t it be a good idea to review clients’ PSCs whenever ongoing monitoring is carried out during a relationship?

At that point of course, the fate was sealed. So it came to pass: the Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (Amendment) (No. 2) Regulations 2022 reintroduced the need to review PSCs as part of ongoing monitoring.

How frequently should these reviews be carried out?

The MLR17 indicate that the primary purposes of “ongoing monitoring” are to examine whether a client’s activity is consistent with what the AML-regulated business expects it to be based on its knowledge and risk assessment and to ensure that the AML CDD measures remain up to date.

Neither the MLR17 nor the CCAB Guidance specify how frequently “ongoing monitoring” should be conducted. As with most things AML, the MLR17 state that it needs to be done according to the assessed risk. In a fairly recent ICAEW webinar directed at ICAEW members in general (c.1 hour into “Money Laundering Risks”, March 23), it was suggested that periodic routine ongoing monitoring might be done every year for high risk clients and every two or three years for low risk clients.

Of course, the mood music from the RPBs has been that insolvency is generally a high risk service, so IPs are unlikely to have any truly low risk clients when compared with accountants. Therefore, in insolvencies, it seems to me sensible to tick the “ongoing monitoring” boxes at the time of each case review, but of course firms are free to establish policies setting out other timescales.

Do these reviews realistically achieve anything in insolvencies?

In almost all cases, I think not. For example, you would not expect PSCs to change in a CVL. The only cases where I can imagine a PSC ever changing are rescue Administrations or CVAs, but even then it would be very rare. I guess potentially it could also happen in an MVL, although most shareholder-shifting occurs pre-liquidation.

I understand that part of the authorities’ concerns generally is that some fraudsters file director-appointment or PSC-registration documents on Companies House in order to build a false identity. Although one would hope that directors would police their own company’s file at Companies House, AML-regulated businesses are also tasked with keeping the registers clean by means of these statutory PSC reviews and discrepancy reporting requirements.

But how likely is it that a fraudster is going to pick an insolvent company in order to build a false identity?

Hopefully, the long-awaited Companies House reform measures via the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill, which is currently being considered by the House of Lords, will block the ability for fraudsters to abuse company files in this way in future. But I suspect that this will not mean that the PSC requirements on professionals are lifted (sigh!).

HM Treasury micro-management: requirements on record-keeping

If the issue were just that we needed to check the PSC register at every ongoing monitoring point, I could just about live with that. However, the amendments go further than this. In a seemingly unprecedented demonstration of micro-management, we are now required to take a copy of the PSC register every time ongoing monitoring is carried out!

This is set out in new Regulation 30A(2A):

“When taking measures to fulfil the duties to carry out customer due diligence and ongoing monitoring of a business relationship.., a relevant person must also collect an excerpt of the register which contains full details of any information specified in paragraph (1A) which is held on the register at that time, or must establish from its inspection of the register that there is no such information held on the register at that time.”

But now we only need to report “material discrepancies”, right?

True, the regulators have highlighted this particular change as lessening the burden on us all. But the small print suggests to me that little has changed in practice.

While the Regs have been changed so that only material discrepancies need to be reported, new Schedule 3AZA defines these as occurring where:

“… the discrepancy, by its nature, and having regard to all the circumstances, may reasonably be considered—

(a) to be linked to money laundering or terrorist financing; or

(b) to conceal details of the business of the customer.”

Companies House guidance on Reporting a Discrepancy points out that it is irrelevant whether there was an intention to conceal.

The Regs’ Schedule continues:

“Discrepancies listed in this paragraph are in the form of—

(a) a difference in name;

(b) an incorrect entry for nature of control;

(c) an incorrect entry for date of birth;

(d) an incorrect entry for nationality;

(e) an incorrect entry for correspondence address;

(f) a missing entry for a person of significant control or a registrable beneficial owner;

(g) an incorrect entry for the date the individual became a registrable person.”

In my experience, incorrect natures of control or entirely missing entries are the most obvious discrepancies, so these will continue to need to be reported.

The Companies House guidance on Reporting a Discrepancy provides examples of discrepancies that would be considered “material” and it seems to me that only insignificant typos might not hit this threshold. I guess, however, that we might also avoid reporting a discrepancy if someone is registered as a PSC when they are not one… although I wonder how the RPBs will view this.

What a faff!

What happens after a PSC discrepancy report is submitted?

Well, the Regs require Companies House to “take such action as [Companies House] considers appropriate to investigate and, if necessary, resolve the discrepancy in a timely manner” (MLR17 Reg 30A(5)). In practice this appears to mean that they will email the insolvency office holder and ask them to amend the company’s register. Personally, I cannot see that there is a positive duty on an insolvency office holder to fix the register and, in any event, the PSC discrepancy report is only submitted on the basis of the IP’s knowledge; in many cases, the true facts of the situation may be less than certain.

If the IP chooses not to amend the register, then the chances are that the discrepancy will remain. I have seen that, in such cases, Companies House generally takes the view that they have taken the appropriate steps and so no more action is required. Oh, the things we all do to comply with poorly thought-out legislation!

A welcome bit of pragmatism in the Companies House guidance

Of course, things tend to be different with a live client, such as those with accountants. In those cases, when an accountant identifies a PSC discrepancy, it would be usual for them to get in touch with the client and encourage them to correct the discrepancy on the file. Although this sometimes also happens pre-insolvency, in cases where the PSC discrepancy remains after the insolvency has begun, this gives rise to another issue when “ongoing monitoring” is carried out later.

Technically, the amended Regs don’t accommodate an uncorrected PSC discrepancy. They would require you to submit a new PSC discrepancy report every time.

However, the Companies House guidance on Reporting a Discrepancy thankfully explains that they are not expecting a second discrepancy report if it has been reported previously.

Should the insolvency office holder be recorded as a PSC?

Interesting question, don’t you think? Clearly, insolvency office holders exercise “significant influence or control”, so does this make them a PSC? As their appointment doesn’t immediately affect the PSC register at Companies House, does this give rise to a material discrepancy to be reported during ongoing monitoring or a need to be registered as a PSC on appointment?

I strongly recommend the Companies House guidance on “Significant Influence or Control”. It contains many nuggets helping to determine who might be a PSC.

It includes, at para 4.4, that anyone exercising a function under an enactment, e.g. “a Liquidator or receiver”, is not a PSC (provided that they only act in accordance with their statutory functions).

That’s one issue sorted, then.

When PSCs and Beneficial Owners differ

But there are other scenarios that can be confusing. In most cases, identifying the PSCs is no different from identifying the beneficial owners for AML CDD purposes and this makes it relatively straightforward to spot any PSC discrepancies.

But there are several situations in which the PSCs are not the same as the AML beneficial owners, so when staff are checking for PSC discrepancies it is valuable that they understand these anomalies.

When there is a UK-registered corporate shareholder

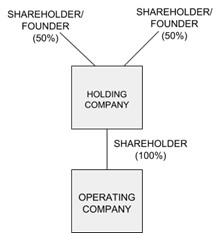

Sometimes, we come across the following scenario:

We’re probably all comfortable with the concept that the beneficial owners for AML CDD purposes are the two 50% shareholders at the top of the tree. However, if the holding company is a UK-registered company, then the holding company is the one that should be registered as the operating company’s PSC.

There are other scenarios (i.e. not only UK-registered companies) where a 25%+ shareholder who is a legal entity should itself be registered as a PSC – see section 2.2. of the Companies House PSC guidance for companies. But in other cases, the legal entity shareholder should not be registered as the PSC, but instead the individuals or entities up the shareholding tree need to be registered.

Where the shareholder has died

For AML CDD purposes, the MLR17 state (Reg 6(6)):

“In these Regulations, ‘beneficial owner’, in relation to an estate of a deceased person in the course of administration, means—

(a) in England and Wales and Northern Ireland, the executor, original or by representation, or administrator for the time being of a deceased person;

(b) in Scotland, the executor for the purposes of the Executors (Scotland) Act 1900”

However, the Companies House PSC guidance for companies states (para 7.7.1):

“In the unfortunate event that a PSC of your company is deceased, the PSC should remain on the PSC register until such time as their interest is formally transferred to its new owner. While an executor has fiduciary duties to the intended beneficiaries of the assets, the executor is are responsible for administering the estate according the wishes of the deceased. The deceased will therefore continue to be registrable until such time as the control passes to another person, such as an heir, who will exercise their influence and control over your company for themselves.”

In other words, for AML CDD purposes, the executor or administrator of a deceased person’s estate will be a beneficial owner, but for PSC purposes it will remain the deceased person.

The difference between “significant” and “ultimate” control

While we usually focus on the shareholders and directors when identifying the beneficial owners for AML CDD purposes, there is an additional woolly category (MLR17 Reg 5(1)(a)): those who “exercise ultimate control over the management” of the entity.

The PSC regime has a different measure. As the name suggests, it is concerned with those who exercise significant, not ultimate, control. I think that both the AML and PSC regimes require us to consider shadow directors, but other people may be a PSC but not a beneficial owner.

The Companies House guidance on “Significant Influence or Control” includes an interesting – and insolvency-relevant – example (para 4.10):

“Extra-ordinary functions of a person could result in them being considered to have significant influence or control:

A director who also owns important assets or has key relationships that are important to the running of the business (e.g. intellectual property rights), and uses this additional power to influence the outcome of decisions related to the running of the business of the company. This individual would not be able to rely on the excepted role of director to avoid being considered to exercise significant influence or control.”

This scenario – and indeed the existence of shadow directors – could make an IP’s life frustrating, I think. Before appointment, you could identify someone exercising significant control in this way but who is not registered as a PSC at Companies House… so you submit a PSC discrepancy report. Then, Companies House gets in touch with you after your appointment asking you to amend the register. But at that point, the person no longer exercises significant control – ta daa!

Ok, I know, I would hope that the RPB would not take you to task for not submitting a PSC discrepancy report pre-appointment, but who knows?

The costs of compliance

IPs are well accustomed to investing time and effort in complying with what appear to be pointless requirements, so I’m sure that most will read this with a tired eye-rolling.

Of course, all these additional duties need to be resourced and this costs firms – and therefore insolvent estates – more money. However, it seems that the RPB/IS perceptions that some IPs charge excessive fees never change, regardless of the fact that year after year compliance duties increase. This may only be another 10-minute task, but it all adds up, doesn’t it?