There’s no doubt that the RPBs have stepped up scrutiny of RP14/15 forms in recent months. In this blog post, I explore what the Acts and Dear IP actually require when it comes to “verifying” RP14/15 data and the measures you can take to protect yourself from RPB criticism that you’re not doing enough.

An important resource on this subject is Dear IP chapter 11, found at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/dear-insolvency-practitioner/11-employment-issues

What does the legislation require?

The Employment Rights Act 1996 and the Pension Schemes Act 1993 use similar language. They require you to notify the RPS of the amount of debt that “appears” to be owed (S187(1) ERA96 and S125(3) PSA93).

However, the RP14/15 forms use much stronger language.

What do the RP forms require?

The RP14 form requires the office holder to make certain declarations including:

- “This form and any attachments have been completed, and the information given is correct, to the best of my knowledge”

Wow: “best” is a high bar, isn’t it? It doesn’t allow room even for inadvertent errors.

The RP15 form includes a similar declaration:

- “The information given in this form is correct and complete to the best of my knowledge.

- “I have examined the claim, including the RP15A spreadsheet and the actuarial certificate if applicable, in accordance with section 125 of The Pension Schemes Act 1993”

The above reference to “examined… in accordance with section 125” seems odd, given that S125 includes the far woollier “appears to be” wording, but hey ho.

The RP14 warning

The RP14 form includes a warning that I guess the RPS is hoping will make IPs stop and think:

- “NOTE: This information is required under section 190 of the Employment Rights Act 1996.

- “Any refusal or wilful neglect to provide any information required by the Secretary of State, and any false statement made knowingly or recklessly in response to this requirement, may amount to a criminal offence under that section.”

Personally, I question whether this threat has any teeth. My reading of S190 is that the criminal offence can only be committed by “the employer” who provides false information or by anyone who does not cooperate in producing documents and, while S190 states that a director or similar officer can be culpable for a body corporate’s failure, it still seems to me a bit of a stretch to squeeze an office holder into this section.

But of course I would not want to chance it and in any event we don’t need the threat of a criminal conviction to persuade us to be diligent in our work, do we? If nothing else, we need to comply with the Insolvency Code of Ethics’ fundamental principle of professional competence and due care.

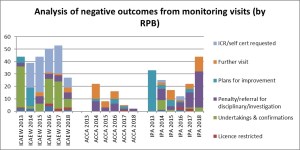

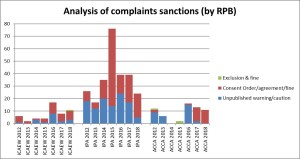

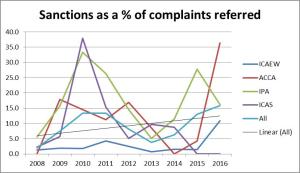

RPB sanctions

Breach of this fundamental principle tends to be the primary allegation on which RPB disciplinary sanctions are made in this area. Over the past 6 months, three relevant RPB sanctions have been published:

- IPA (Aug-23)

- Failed to ensure that a complete and accurate RP15 was submitted

- Fined £2,000

- ICAEW (Oct-23)

- Failed to inform RPS that the IP had not verified employee claims (and other unrelated failures)

- Fined £5,000

- IPA (Nov-23)

- Failed to take sufficient steps to verify employees’ claims and to carry out independent verification of information provided by directors before submitting RP14As and failed to raise any concerns with the RPS as to the veracity of the employees’ claims

- Fined £10,000

Why has this become such a hot topic?

Protecting against fraudulent claims

All the way back in October 2008, Dear IP warned us to be on the look-out for fraudulent claims (chapter 11 article 27). More recently, in December 2020, a more in-depth Dear IP was issued (chapter 11 article 70) flagging up the warning signs for potential fraud. This article is well worth another read.

Alarmingly, it appears that some companies have been operated perhaps solely for the purpose of extracting fraudulent payments from the RPS. Even some legitimately trading companies may have ghost employees on their books. But also fraud can be at the lower level, where individuals’ rates of pay or outstanding holiday entitlements are exaggerated.

Not all the warning signs noted in the Dear IP will be spotted from a company’s records. But what work are IPs expected to do?

Where does the “verification” requirement come from?

As we have seen, the need to “verify” information does not appear in the legislation or on the RP forms. Where does this idea come from?

It seems to derive from Dear IP chapter 11 article 27, which states:

- “RPS assumes that the information on the RP14a has been verified from the employer’s records before it is sent to the RPS.”

Thus, if you receive information from any source other than the employer’s records, the assumption is that this information has been verified against the employer’s records. In my experience, the RPBs seem to have converted this into a requirement, with the IPA taking the strictest line. Where I have referred in this article to the RPBs, generally I mean the IPA.

Are you expected to verify all data?

Interestingly, Dear IP chapter 11 article 70 suggests not necessarily:

- “Insolvency Practitioners are reminded that they should make an assessment on a case-by-case basis to decide what reasonable checks are necessary to verify information or identities before submitting the RP14/14A to the RPS.”

Of course, you would need to have documented this assessment for the file – and it is open to an RPB to challenge such an assessment as falling short of showing professional competence or due care – but this Dear IP does appear to allow an IP to decide that verification of alldata may not be reasonable in every case.

However, in my experience, the RPBs appear to be starting from a default that all data – that is, every piece of data for each employee on the RP14A/15A – need to be verified if at all possible. After all, isn’t that the only way you are going to be able to declare that the data is “correct to the best of my knowledge”?

A variety of data sources

Ok, so the ultimate data source is the employer’s records. But sometimes the records just aren’t sufficient, are they? For example, holiday entitlement data can be sketchy and sometimes non-existent in the records and many employees have a better grip on what overtime or commission they’re owed.

Are there any other acceptable sources of information?

Is it ok to use data on a spreadsheet completed by the director/employee?

It is fairly common practice to provide a pro forma spreadsheet to a director or payroll person, usually pre-appointment, and ask them to complete it with all the employee data.

This may seem a practical way to compile data from a variety of company records that the director/employee knows inside-out. However, going by the RPBs’ recent activity, this triggers the Dear IP need for you to “verify” the data against the company’s records. This pretty-much defeats the object of getting someone else to complete the spreadsheet for you, doesn’t it?

Is it ok to rely on information from pension providers?

Again, this is a fairly common practice, not least as the RP15 form expects the RP15A to be completed by the pension provider. However, the RPBs are expecting the RP15A data to be verified against the employer’s records.

Is it ok to rely on RP14As/15As drafted by employment specialists?

It appears not. Even where the specialist has been instructed by the office holder to act as their agent, the RPBs appear to be expecting all data on the forms to be verified against the employer’s records. The argument is: how else can the IP sign off the form as correct to the best of their knowledge?

In my mind, this seems a step too far. Surely the RPB doesn’t expect an IP personally to cross-check all the data on an RP14A/15A form against the company’s records where one of their staff have completed the form, do they? But how is this different from their agent, an external specialist, completing the form?

I asked an Insolvency Service person this question. They maintained that, in order for the IP to make the declaration, the IP must have some basis on which to form an opinion that the data is correct, so this would require some cross-checking. However, they did at least agree that it need not be all data.

Is it ok to ask the employee direct or to draw information from the RP1?

I’m sure you can guess my answer: nope, not without verifying the information against the company’s records.

However, Dear IP (chapter 11 article 70) does provide a precedent for this:

- “Where there is insufficient evidence in the records, IPs should not use the RP1 data to complete the RP14A entry without contacting RPS first to discuss. In the absence of that discussion RPS will assume that there is evidence in the records to substantiate the RP14A”

There’s the instruction: if you have no alternative, then contact the RPS first and discuss with them the last resort of relying on the RP1 data.

What if the company’s records conflict with what an employee says they are owed?

I have heard stories of, not only employees, but also RPS staff badgering IP staff to submit an amended RP14A so that an employee’s claim can be processed. Of course, while there may be legitimate reasons for amending an RP14A where you are satisfied that the RP14A is wrong, what if you’re simply being told by the employee that the company’s records are wrong or incomplete?

With all the emphasis on preventing fraud and relying on the company’s records, I wonder what would happen if you just said no, you’re not prepared to amend the RP14A.

S187(2) ERA96 and S125(5) PSA93 empower the RPS to make a payment without the office holder’s “statement”, so you should not be held hostage with the threat that an amended RP14A is the only way the employee is going to get paid. You will have submitted the original RP14A to the best of your knowledge, having verified the information as far as possible against the company’s records, so why change your mind on the employee’s say-so?

But what if you just don’t have sufficient company records?

Well, as mentioned above, if you are drawing information from an RP1, Dear IP instructs you to discuss this first with the RPS.

In all other scenarios where you use data other than that drawn directly from the employer’s records, I recommend that you notify the RPS of this action when you submit the RP14/15.

In my mind, if you use data from another reasonable source, it could still be what “appears” to be owed and it could be “correct to the best of your knowledge”, provided that you truly do not have in your possession any other more reliable knowledge, e.g. from company bank statements, that you haven’t checked against. The RPB sanctions above also illustrate that notifying the RPS of the limitations of your verification work is an acceptable step.

How exactly should you verify data?

As with all things in insolvency administration these days, I think it comes down to having an established procedure and checklist to document the work done and decisions made. Here is my 6-step process.

1. Document the information you obtained, i.e. each item of data required by the RP14A or RP15A. It would also be wise to follow Dear IP chapter 11 article 81, which sets out the RPS’ approach to directors’ claims: as the office holder signing off an RP14, you need to satisfy yourself that a director’s claims as an employee are substantiated and so it would seem reasonable to apply the same rationale as the RPS and to document your decision in this regard

2. Document the source(s) of each part of the information, i.e. if it were not all in the company’s records, how did you plug each gap?

3. Check information against the bank statements, e.g. who was paid by the company, what were they paid and when were they – and the pension scheme – last paid?

4. Note whether the company records support each item of data and, if not, what you are relying on

5. Note the bases for calculating the weekly pay and holiday rates for employees with variable rates of pay (see e.g. Dear IP chapter 11 article 72) and how you have calculated holiday entitlements

6. Tell the RPS everything, in particular the extent of your verification work and the source(s) of information where the employer’s records were insufficient

At the Compliance Alliance, we have created a checklist covering these steps and we recommend that the completed checklist be sent to the RPS at the time of submission of an RP14/15 form.

Finally also you need to keep abreast of the legislation. For example, Dear IP chapter 11 article 82 noted several 2023 SIs that may affect the definition of “wages” or “weekly pay” and other Regulations will affect holiday pay calculations (Employment Rights (Amendment, Revocation and Transitional Provision) Regulations 2023). Alternatively, instruct employment specialists to assist. This can take much of the pain out of the process.

That’s a crazy amount of work?! Are the RPBs aware of how this impacts on time costs?

I asked an Insolvency Service person this question. They appreciated that substantial time could be required to carry out this verification work. They maintained that the RPS has a duty to ensure that payments from the NI Fund are accurate and they are therefore looking to IPs to help by providing accurate RP14/15 data.

The common theme in all this is: how else can you declare that the information you have provided on an RP14/15 is correct to the best of your knowledge?

I recently presented a webinar on this topic to clients of the Compliance Alliance. You and all your colleagues can get access to a recording of this webinar, along with access to all the recorded webinars in our library and c.10 future webinars, for £350 + VAT for one year. For enquiries, please email info@thecompliancealliance.co.uk.